Software Quality Assessment and Testing (QA) is going through an identity crisis, manifesting in many QA professionals as generalized uncertainty.

We’re uncertain about the value and future of QA. We’re uncertain about differences between testing and automation. We’re uncertain about our place in the organization and how to advocate for our needs. We’re uncertain how to measure our impact on business success. We’re even uncertain about a fundamental concept for the entire industry: quality.

The uncertainty of quality stems from a debate about the source of goodness. Either “the good” is a set of intrinsic attributes we can’t enumerate, or “the good” is a complex set of subjective relationships we also can’t enumerate. Framing the problem of quality as a conflict between two ultimately unknowable forms of goodness drives the consequences we witness today. Motivating QA to position itself around what we can’t do: we can’t define quality, we can’t measure quality, we can’t improve quality and we certainly can’t ensure quality. To reverse this trend, we can’t continue with this old debate, we need a new answer to the question “What is quality?”.

In this article I’ll present my answer, and the approach I take on the topic of quality. I will reaffirm the first principle that makes QA possible and explain the set of concepts I use to describe the interplay between people and products, including value, disvalue, quality and trade. I’ll conclude with a discussion of the role QA can play in driving business outcomes within a software organization. With that as a foundation I believe we can shift QA from cost center to strategic partner.

Identity

The assumption underlying work in QA is identity, which is an ontological concept meaning the fact of being what a thing is. The product is what it is at any given time, including its qualities, effects, and capacity to change. This concept doesn’t specify what a product is in particular; it identifies the fact that if a product exists, it is something.

If we assume the opposite, that a product is nothing in particular, then asking for facts, proof, or evidence is meaningless. Facts about what? Proof related to what? Evidence of what? In such a state, anyone could say anything about the product, at any time, with no method or means of validating the claims. Facts, evidence, and proof; presuppose a product is something that can be tested, measured, and identified.

Because the product is something specific it also has definite effects on those who use it. In order for people to identify these effects and describe their impact, we’ve developed language that I conceptualized into two classes: value and disvalue.

Values and Disvalues

A value is a desired effect caused by an interaction between a person and other people, or objects. I assume most agree the following short list represents some common values; love, entertainment, nutrition, taste, and pride. Some of these values are direct effects, like taste, others are abstract concepts combining several effects, like love. Regardless how concrete or abstract, these values involve interactions between peoples and objects of one kind or another. We live, laugh, hug and cry with our partners, friends and families to gain and maintain the effect of love. We watch movies, read books and swipe Ticktok to gain the effect of entertainment. We eat food to gain the effects of nutrition, and enjoyable taste. We build great products to solve problems and gain the effect of pride. But where there is value there is also disvalue.

Disvalue is the inverse of value. It is an undesirable effect we want to remove or avoid. We end toxic relationships, stop watching boring movies, avoid food that makes us sick and report bugs in software that prevent us from completing goals.

When asked about a product, a non-expert is likely to express their understanding of these effects in terms of values, and disvalues, what they like and what they don’t. These are the effects they notice because, for better or worse, those effects impact them. A customer may go as far as describing their experience as quality, while not knowing anything else about the product. This is ok, it's not their job to know more about the product, or the technical meaning of quality.

QA faces challenges when we conflate quality with the desirable effects customers seek from the product. We forget that both values and disvalues are important considerations for customers. Further, we forget that values and disvalues are a customer's method of expressing their understanding of a product's attributes and effects. We lose the ability to talk holistically about the product. In extreme cases we abandon the concept of quality completely, because it’s too subjective and imprecise to focus on.

We must not do this, it's essential to understand that quality, value, and disvalue are distinct but related concepts that play a vital role in ensuring customer satisfaction, product and business success.

Quality

To stress the point, quality is not “value to someone who matters” as Jerry Weinberg would put it. Quality does not denote goodness and is not an attribute or relationship of a product. Quality is an individual’s knowledge about something, for example, a person, product or process.

Quality is the epistemological sibling of identity. Identity does not specify what a thing is, only the fact that if it exists it is something. Likewise, quality does not specify what is known or who knows it, only the fact that if something is known, it’s known by someone and about something. Instances of identity are discovered when you experience and study a product. That knowledge is an instance of quality. Let me illustrate.

A small business owner looking to build a website studies the product and finds templates, ecommerce capabilities, fast customer support and a buggy blog platform. This is an example of quality.

An enterprise customer studying the same product finds SOC2 compliance, 99.99% uptime, performance problems and lack of localization capabilities. This is an example of quality.

A junior QA studying the product discovers a security vulnerability in account creation, a system crash when adding a new webpage, and fast publish times. This is an example of quality.

Assuming no one in these hypothetical scenarios is lying, all of these instances of quality are valid and true. They each identify something factual about the product and its surrounding context. The fact people focus on different aspects of the product and have a unique experience does not matter for the concept of quality. These differences in knowledge and language do not invalidate any of the positions. New knowledge does not contradict old knowledge but rather expands it. The work of understanding quality is about combining all these sources of knowledge into one integrated whole.

To tie value and disvalue back into this discussion, people come to value judgments about the product after they integrate quality with other knowledge about their life. This integration process is continuous and lightning-fast. Even from a position of limited knowledge, say, hearing about a product in passing, people will take that knowledge and form a value judgment. As they learn more, through ads, community, or direct experience, this new knowledge will alter their value judgments. Likewise if their lives change, that new reality will alter their value judgment just the same. However, that new life knowledge does not impact quality — their knowledge about the product. The point here is that some knowledge of the product must come first before a value judgment can be formed since the product is the subject of judgment. The speed of this integration can make it hard to distinguish between quality and value, but we must acknowledge the order of operations. This interplay between quality and value judgments is the complexity underpinning trade.

Trade

Business is all about trading, exchanging value for value with its customers and employees. However, in all complex relationships, there is also disvalue. For trade to occur and continue, the value received must outweigh the disvalue more often than not. The complexity and number of these relationships differ from company to company and time period to time period. Here are just a few examples:

The business gets value from its customers: resources in the form of money and pride from delivering a great product. It can also receive disvalue from its customers, such as overtly abusive behavior if things don't go the customer’s way.

The customer gets value from the product: a solved problem, relaxation, entertainment, etc. They can also receive disvalue from the product or business, such as bugs, outages, slow delivery, and unclear or rude communication.

Employees get value from the business, including salary, benefits, and pride in a shared mission. Employees can also receive disvalue through toxic work cultures and building a product that doesn't align with their own standards.

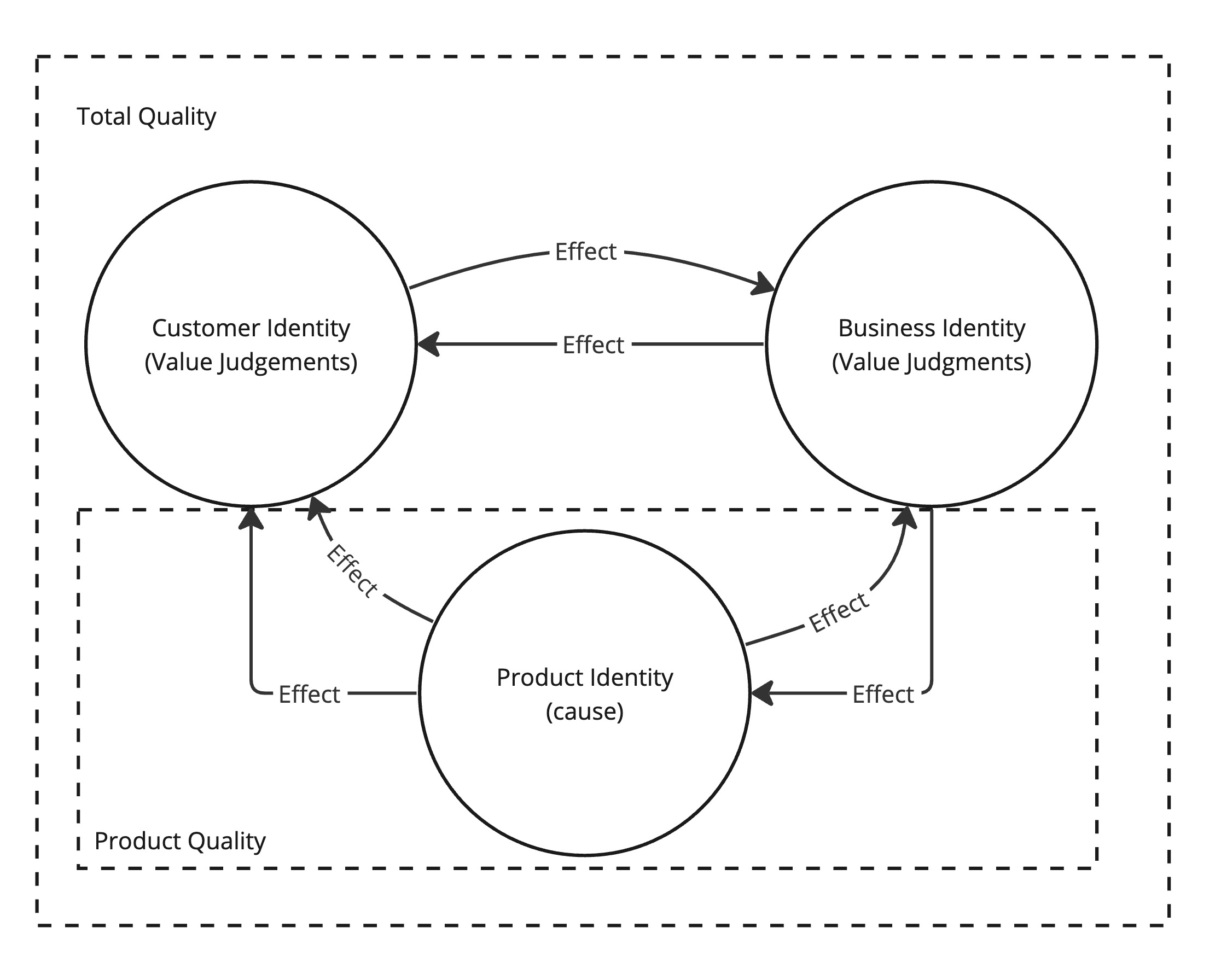

We can study each of these relationships in great detail and link them to more and more relationships, such as suppliers, contractors, investors, and regulators. This complexity represents the core challenge of running any business at any scale. Put another way, the challenge is to have enough customer, business, and product quality to make decisions on what to change to ensure the balance of value is greater than the disvalue.

In this context, total quality means focusing on building knowledge about customers, team members, processes, products, and their interconnected effects.

With that in mind, a company can choose to focus its QA efforts on different aspects of the business. For instance, a business may require a significant amount of attention on product quality, and therefore, it invests in experts who specialize in testing products. Alternatively, a business may need to focus on processes, and it invests in experts who specialize in testing processes. A business may also require a lot of attention on understanding its customers, and so it invests in people who are experts in testing customers. Ideally, a company should invest in all three areas, but for today, my focus is on product quality.

The role of product qa

With identity as its foundation and quality as its focus, QA strives to answer two fundamental questions for the business: What is the product, and how do we know? In doing so, we create and expand product quality. Put another way, we increase the understanding of a product’s identity organization-wide, making visible its qualities, characteristics, attributes, and effects. However, we do not do this aimlessly.

Expanding quality for quality's sake is not a value for a company or customer and should not be the goal of QA organizations. An equivalent example is coding for coding's sake: more code is not inherently better, nor is the sheer volume of information. Quality is information, and producing streams of it with no focus is just noise. The role of QA must be to focus on making quality impactful by connecting it to the business and customer value proposition.

Values are the desired effects customers and businesses want the product to cause. Disvalues are the effects customers and businesses want to avoid. The combination of these two forms a vision for what we want the product to be. Quality is what we know the product is today. To connect quality and value, the QA role is to discover the delta between the actual and potential product. This does not require waiting for requirements to test and discover effects. In fact the discovery of effects is often the precursor to requirements discussion. This is the answer to the question of why a focus on quality is so important.

When identity, quality, and value are connected, business and customer success follow. Investments in quality mean maximizing a company's ability to discover risks and opportunities before it’s too late to act. When a company is empowered to act, it’s in the best possible position to minimize losses and maximize profits while improving value for customers.

This view stands in stark contrast to the idea that the QA role, at best, is to increase process velocity and reduce re-work or, at worst, just not be a roadblock.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the identity crisis that software QA is facing today can only be resolved by adopting a new approach to the concept of quality. Quality is not an attribute or relationship of a product, but an individual's knowledge of it. We must not conflate quality with the desirable effects customers seek from the product, because we lose the ability to connect quality to value. It is time for QA professionals to shift from cost centers to strategic partners and maximize their potential impact on business outcomes. Let us take a new approach to quality and drive the software industry forward towards a brighter future.